In light of the imminent threat of New World screwworm looming along the Texas-Mexico border, we thought a timely update would be in order. With that in mind, we’ve pulled together the following information and resources to help guide you. We plan on regularly sharing updates with you and we welcome any questions you may have.

Louis Harveson

Director, Borderlands Research Institute

Carlos E. Gonzalez, Ph.D., Associate Director of Research and Nau Endowed Professor.

Eduardo A. Gonzalez-V., Ph.D., Visiting Professor and Grazing Specialist.

J. Silverio Avila-S., Ph.D., Assistant Professor and Extension Range Specialist.

The New World screwworm (Cochliomyia hominivorax) has long been one of the most destructive parasites to affect livestock, wildlife, and even humans. While many flies feed only on dead or decaying tissue, the screwworm is different: its larvae consume living flesh. This trait alone makes it uniquely dangerous to ranching operations and wildlife populations across the Americas. For landowners and natural resource managers, understanding the biology of this pest, its devastating impacts, the history of eradication, and the challenges of inhibiting its return is essential.

Female New World screwworm flies lay their eggs in open wounds (e.g., branding marks, castration sites, dehorning cuts, tick bites, or even scratches from barbed wire fences). Within a matter of days, hundreds of larvae may hatch and infest a single wound, tunneling deeper into the tissue as they grow. Mature larvae can reach nearly two-thirds of an inch, their bodies ringed with spines that twist in a corkscrew pattern through flesh. This spiral feeding pattern is what gave the New World screwworm its name. Infested animals experience severe pain, rapid tissue destruction, and secondary infections that, if left untreated, often lead to death. Adult flies, metallic blue with three dark stripes behind their heads and large orange eyes, are fast, fertile, and capable of traveling long distances in search of new hosts. Unlike some pests that target specific animals, New World screwworms can infest all warm-blooded animals including cattle, horses, sheep, goats, deer, pronghorn, bighorn sheep, and even pets, and in rare cases, humans, and birds.

The consequences of New World screwworm infestations ripple far beyond individual animals. Ranchers face direct losses from calf mortality, reduced weight gain, sterility in breeding animals, hide damage, and the constant need for treatment and inspection. Wildlife populations also suffer, with deer, pronghorn, and bighorn sheep experiencing high mortality during outbreaks. In areas where populations are already small, such as those of endangered species, New World screwworm infestations can cause collapses that take decades to recover from, if recovery occurs at all. Rangeland ecosystems themselves are not spared. Loss of wildlife diversity and disruptions in predator-prey dynamics weaken ecological balance, reducing hunting lease values and wildlife tourism opportunities. Animal welfare becomes a significant concern, as infested animals endure prolonged suffering and open wounds, often leading to sepsis. The broader community feels these impacts as local economies tied to ranching, hunting, and tourism struggle to recover. Even human health is at risk, with occasional cases reported that highlight the interconnectedness of livestock, wildlife, and people.

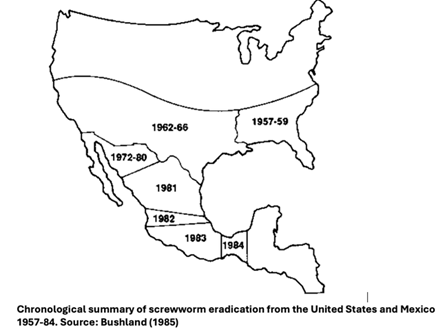

Despite the seriousness of the threat, the history of New World screwworm control offers one of the greatest success stories in applied science and pest management. Beginning in the 1950s, researchers developed the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT). This was a revolutionary method in which male New World screwworm flies were sterilized with radiation and released across infested areas. When sterile males mated with wild females, no viable offspring were produced, and the population declined. Decades of persistent SIT campaigns led to the eradication of New World screwworm in the United States by the early 1980s. Cooperation between the U.S. and Mexico then pushed eradication further south, establishing a permanent biological barrier in Panama. For more than forty years, that barrier has kept New World screwworm from reinvading North America, allowing ranchers and wildlife managers to operate without the constant threat of infestations.

Recent years, however, have demonstrated that the New World screwworm threat is not gone. In 2016, an outbreak in the Florida Keys killed hundreds of endangered Key deer, and only through rapid SIT fly releases, veterinary treatments, and strict surveillance was the outbreak controlled. Since 2023, new infestations have spread through Central America and Mexico, creeping closer to the U.S. border. Recently, reports indicated that New World screwworm was once again dangerously near Texas (located in September 2025 only 70 miles from Laredo, Texas). To delay re-entry, the U.S. has restricted livestock imports from areas affected by the outbreak. Yet such restrictions can only buy time; they cannot fully prevent New World screwworm from eventually crossing the border.

For ranchers and landowners, this should not be seen as a distant concern. New World screwworms directly threaten cattle herds and local wildlife, and a new outbreak could quickly undo decades of hard-earned progress. The tools used to manage New World screwworm require cooperation on multiple levels, from federal programs to individual vigilance. While SIT remains the backbone of regional eradication, landowners play the most crucial role in early detection and response. Regular inspection of cattle, particularly after branding, castration, or dehorning, can catch infestations before they spread. Ranchers must treat wounds promptly, ensure proper healing, and minimize the risk of further injury to prevent complications. Importantly, all maggots within the wound should be killed and removed, since any that fall to the ground can pupate in the soil and emerge as adult flies, perpetuating infestations. Tick control is another preventive measure that reduces the number of wounds that can serve as entry points. Perhaps most importantly, any suspicious infestation should be reported immediately to veterinarians or local officials Rapid reporting enables more effective and coordinated responses, protecting not only individual ranches but also entire regions.

Visit the Screwwormtx.org site to contact Texas Animal Health Commission to report livestock and pet suspicions, or to contact Texas Parks and Wildlife Department to report wildlife suspicions.

Looking ahead, preventing the return of New World screwworm to the U.S. will require continued investment and vigilance. Expanding sterile fly production and release capabilities will likely be necessary to respond quickly to new outbreaks. Education and outreach efforts will remain vital, ensuring that landowners know the signs of infestation and respond quickly when they appear. The story of the New World screwworm is one of both success and warning. Science and persistence once drove this devastating parasite out of the United States. Still, outbreaks in Central America and northern Mexico show that the risk of its return is very real. Landowners and wildlife managers have the most to lose if New World screwworm resurfaces, but they also hold the keys to prevention through vigilance, rapid reporting, and cooperation with control programs. With preparedness and continued commitment, the U.S. can maintain its defenses against this pest and safeguard the health of livestock, wildlife, and communities for generations to come.

Resources to learn more about New World screwworm

- Screwworm Coalition of Texas https://screwwormtx.org/

- TPWD https://tpwd.texas.gov/newsmedia/releases/?req=20250923a&utm

- TAHC https://www.tahc.texas.gov/

- USDA https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/cattle/ticks/screwworm?utm

- TAMU AgriLife https://agrilifeextension.tamu.edu/new-world-screwworm